My daughter has tried a variety of preschool-age activities – soccer, gymnastics, dance, art, etc. The only activity that has stuck is piano. Considering the exploration vs. exploitation trade-off, perhaps it’s better to delay exploring new activities until she’s older and instead exploit her current interest in music. I imagined her having fun playing in a band when she’s older (note: I cannot play a musical instrument), so I bought an electronic drum kit envisioning her as a cool drummer. But then I wondered, “Why are there so few female drummers?”

What is the prevalence of female drummers?

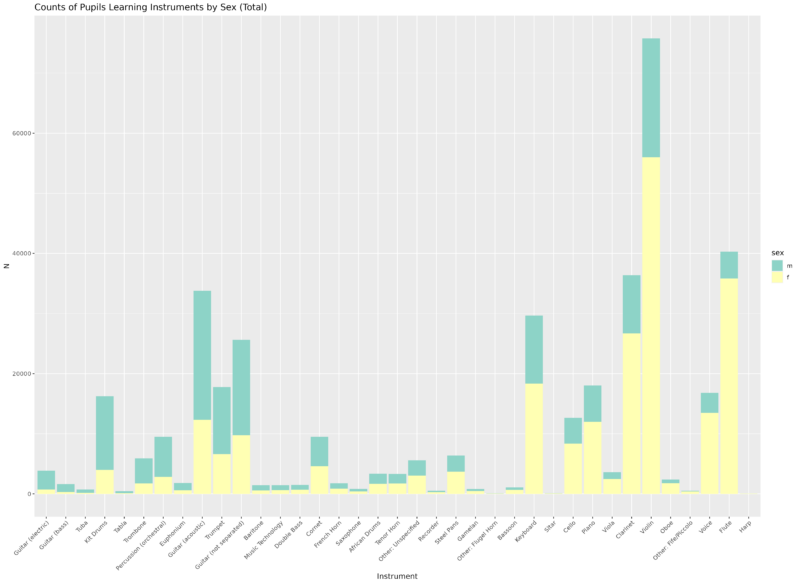

“Survey of local authority music services 2005“1 offers a data set with a large sample size on the sex ratio of musical instruments. Table 3.22 contains counts of the total number of pupils learning each instrument for all age groups, which I recreated as a sortable table below.

| instrument | sex | n | pct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guitar (electric) | male | 3126 | 0.81 |

| Guitar (electric) | female | 725 | 0.19 |

| Guitar (bass) | male | 1306 | 0.81 |

| Guitar (bass) | female | 313 | 0.19 |

| Tuba | male | 562 | 0.77 |

| Tuba | female | 168 | 0.23 |

| Kit Drums | male | 12247 | 0.75 |

| Kit Drums | female | 3982 | 0.25 |

| Tabla | male | 334 | 0.74 |

| Tabla | female | 118 | 0.26 |

| Trombone | male | 4175 | 0.71 |

| Trombone | female | 1734 | 0.29 |

| Percussion (orchestral) | male | 6666 | 0.7 |

| Percussion (orchestral) | female | 2827 | 0.3 |

| Euphonium | male | 1222 | 0.67 |

| Euphonium | female | 596 | 0.33 |

| Guitar (acoustic) | male | 21483 | 0.64 |

| Guitar (acoustic) | female | 12315 | 0.36 |

| Trumpet | male | 11143 | 0.63 |

| Trumpet | female | 6615 | 0.37 |

| Guitar (not separated) | male | 15869 | 0.62 |

| Guitar (not separated) | female | 9745 | 0.38 |

| Baritone | male | 868 | 0.6 |

| Baritone | female | 574 | 0.4 |

| Music Technology | male | 829 | 0.57 |

| Music Technology | female | 615 | 0.43 |

| Double Bass | male | 782 | 0.53 |

| Double Bass | female | 697 | 0.47 |

| Cornet | male | 4888 | 0.52 |

| Cornet | female | 4597 | 0.48 |

| French Horn | male | 888 | 0.51 |

| French Horn | female | 868 | 0.49 |

| Saxophone | male | 421 | 0.5 |

| Saxophone | female | 414 | 0.5 |

| African Drums | male | 1683 | 0.5 |

| African Drums | female | 1680 | 0.5 |

| Tenor Horn | male | 1585 | 0.48 |

| Tenor Horn | female | 1723 | 0.52 |

| Other: Unspecified | male | 2558 | 0.46 |

| Other: Unspecified | female | 3038 | 0.54 |

| Recorder | male | 243 | 0.45 |

| Recorder | female | 292 | 0.55 |

| Steel Pans | male | 2687 | 0.42 |

| Steel Pans | female | 3687 | 0.58 |

| Gamelan | male | 331 | 0.41 |

| Gamelan | female | 467 | 0.59 |

| Other: Flugel Horn | male | 34 | 0.39 |

| Other: Flugel Horn | female | 54 | 0.61 |

| Bassoon | male | 417 | 0.38 |

| Bassoon | female | 676 | 0.62 |

| Keyboard | male | 11306 | 0.38 |

| Keyboard | female | 18352 | 0.62 |

| Sitar | male | 43 | 0.37 |

| Sitar | female | 72 | 0.63 |

| Cello | male | 4301 | 0.34 |

| Cello | female | 8351 | 0.66 |

| Piano | male | 6044 | 0.34 |

| Piano | female | 11982 | 0.66 |

| Viola | male | 1117 | 0.31 |

| Viola | female | 2489 | 0.69 |

| Clarinet | male | 9680 | 0.27 |

| Clarinet | female | 26696 | 0.73 |

| Violin | male | 19763 | 0.26 |

| Violin | female | 56000 | 0.74 |

| Oboe | male | 605 | 0.25 |

| Oboe | female | 1787 | 0.75 |

| Other: Fife/Piccolo | male | 111 | 0.21 |

| Other: Fife/Piccolo | female | 412 | 0.79 |

| Voice | male | 3312 | 0.2 |

| Voice | female | 13479 | 0.8 |

| Flute | male | 4472 | 0.11 |

| Flute | female | 35823 | 0.89 |

| Harp | male | 6 | 0.1 |

| Harp | female | 52 | 0.9 |

I graphed the counts of pupils for each instrument in the stacked bar chart below. The most popular instrument is the violin, followed by the flute. Fewer people are learning drums and bass compared to guitar, explaining why drummers and bassists are harder to find than guitarists when forming a band.

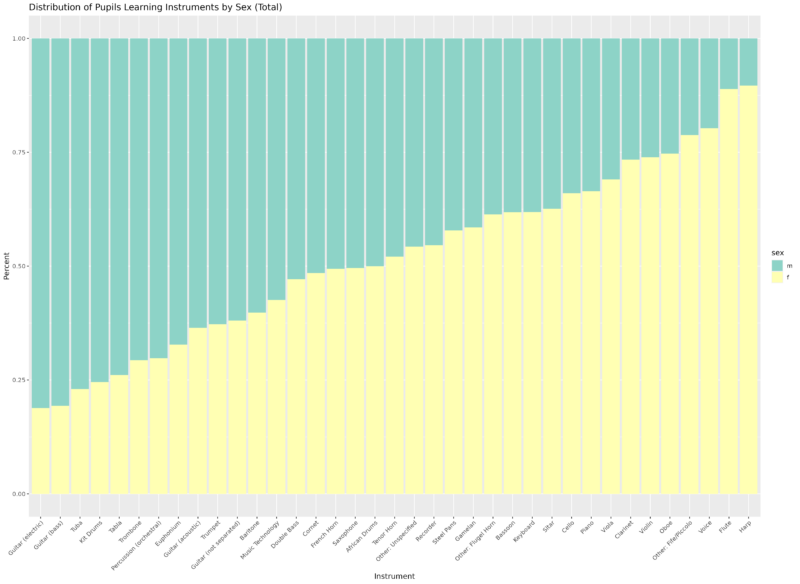

Calculating the sex distribution within each instrument yields the figure below. Instruments are ordered from lowest female percentage to highest female percentage. Drums are the fourth-most male-dominated instrument after the electric guitar, bass, and tuba. Drums are 75% male and 25% female for a 3:1 male:female sex ratio.

The authors of the survey study wrote another paper entitled “Gender differences in musical instrument choice“2 with similar observations. Quoting the abstract of the paper (emphasis mine):

Historically, there have been differences in the musical instruments played by boys and girls, with girls preferring smaller, higher-pitched instruments. This article explores whether these gender preferences have continued at a time when there is greater gender equality in most aspects of life in the UK. Data were collected from the 150 Music Services in England as part of a larger survey. Some provided data regarding the sex of pupils playing each instrument directly. In other cases, the pupils’ names and instruments were matched with data in the national Common Basic Data Set to establish gender. The findings showed distinctive patterns for different instruments. Girls predominated in harp, flute, voice, fife/piccolo, clarinet, oboe and violin, and boys in electric guitar, bass guitar, tuba, kit drums, tabla and trombone. The least gendered instruments were African drums, cornet, French horn, saxophone and tenor horn. The gendered pattern of learning was relatively consistent across education phases, with a few exceptions. A model was developed that sets out the various influences that may explain the continuation of historical trends in instrument choice given the increased gender equality in UK society.

Hallam, Susan, Lynne Rogers, and Andrea Creech. “Gender differences in musical instrument choice.” International journal of music education 26.1 (2008): 7-19.

Thus, there are significant gender biases in musical instrument selection, leading to a lower number of girls learning drums at the top of the funnel.

Representation of Women Drummers in Popular Music

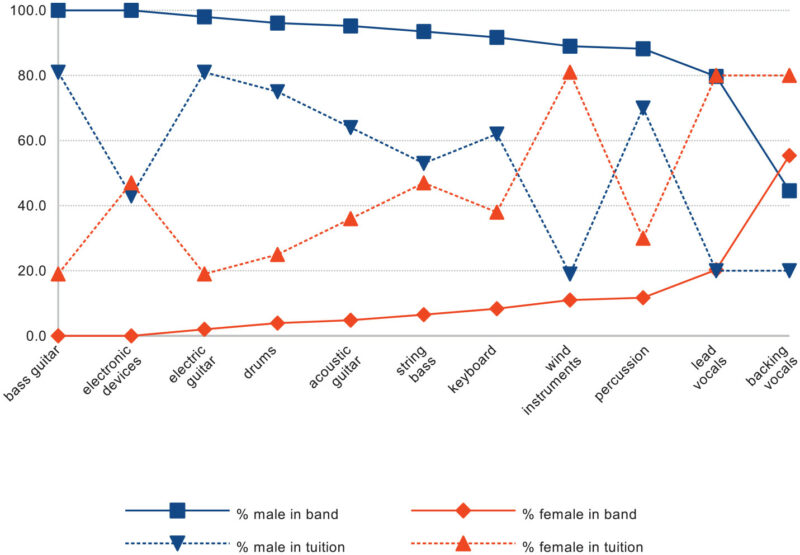

“Performing sex: The representation of male and female musicians in three genres of music performance“3 examined the percentage of male and female musicians in world class orchestras, competition brass bands, and popular music groups. Since I’m interested in number of female drummers, I’ll focus on the pop music results. Quoting from the paper:

Information on popular music groups and their member artists was extracted from data published in February 2017 by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in which are listed those certified record albums that have each sold in excess of 10 million copies. Popular music styles covered by the resulting list included the following: “Pop/Rock,” “Rhythm and Blues (R&B),” “Hip-hop,” “Rap,” “Country and Western,” “Blues,” “Indie,” “Big-band/swing,” “Alternative,” and “Heavy metal.” Details of the performance roles of individual artists in each performance group were obtained from credit listings for recordings published with the recordings at point of sale or on relevant reliable websites. Only performing musicians were included in the data: persons listed as contributing to recordings in non-music-performance roles such as technicians, computer programmers, producers, or in executive roles were excluded, as were the few unusual examples where non-group-member artists contribute to a particular item in an album, as for example in one instance, the chorus of the Metropolitan Opera supported a passage. To avoid artificial inflation of data, groups who had achieved the “10m copies” criterion with multiple albums, as for example, the Beatles, were counted once only. The resulting data covering 62 artist groups represents 788 artists and over 914,000,000 CD sales (Table 3, Figure 18).

A typical “pop group” comprises four players: lead guitar, rhythm guitar, bass guitar, and drums/percussion with at least one of the members providing vocals (Finnegan, 2007) though there are many variant of this format, often including keyboards. Originally, the bass line was provided through acoustic string bass, but in the 1960s, this became replaced by the electric bass guitar (Brewer, 2003).

Sergeant, Desmond C., and Evangelos Himonides. “Performing sex: The representation of male and female musicians in three genres of music performance.” Psychology of Music 51.1 (2023): 188-225.

The figure below is from the Sergeant paper. The solid orange line is the percent of women playing that instrument in a successful popular music group per their inclusion criteria. The dashed orange line is the percent of women learning that instrument, showing data from the Hallam studies above. The representation of women in pop music does not match the representation of women learning those instruments. Women playing guitar, bass, and drums are essentially non-existent in commercially successful pop music.

The discussion section is the most interesting part in the paper. It theorizes reasons why female representation is low at the highest levels of music (i.e. the bottom of the funnel). I won’t cover all of the reasons in depth (sexism, male aggressiveness and dominant behavior with the electric guitar, feminism, studio vs. classical singing style, bias in the music press, bias in the recording industry, portrayal of women in music videos) as these are all weighty topics addressed at the societal level. I will highlight their section on sex differences in music education because that is something I can influence at the individual level:

The Hallam et al. database (Hallam et al., 2005) shows that tuition on instruments of popular music is offered within state-funded provisions for music education, but how much this affects the performer population of the popular music industry is uncertain. Becker, in his forward to H. S.Bennett’s (2017) “On becoming a rock musician,” suggests that rock music is learned but rarely taught. The customary route to acquisition of instrumental skills is by receiving tuition from a professional teacher, but unlike classical musicians, rock musicians need membership of a group to develop. Even participation in a “garage band” enables members to share practical skills and musical knowledge, members constructing their own collective form of knowledge through which they progressively achieve success. But even this process has sex polarities: from her extensive interviews with popular musicians, Green (2002) reports that boys form bands earlier than girls (boys circa age 15, girls from age 21) so boys are likely to have acquired extended band experience by the time that girls normally begin. A. Bennett (2018) and Clawson (1999a, 1999b) both confirm this differential pattern. Our data (Figures 25 and 26) show that girls more often follow the orthodoxy of instrumental lessons during school ages, perhaps following parental and societal expectations, before making their way into popular music; boys are more inclined to gain their first musical experiences directly in popular music from the start without a preface of classical lessons.

H. S.Bennett (2017) proposes that this creates fundamental gender differences in the structural experiences of the nature of music. Boys tend to bypass the tradition of music stored, taught, and transmitted by written notation, building experientially an aural notation derived from experimentation and discovery and from listening to recorded examples. He argues that this establishes alternative ways in which music is stored and analyzed in the brain: memory traces replacing visual retrieval from the written page. Becoming a rock musician, he argues, is not a process steeped in the history, theory, and pedagogy of prestigious academies, or guided by a tradition of teaching and teachers but is learned to a greater extent than it is taught by teachers.

Sergeant, Desmond C., and Evangelos Himonides. “Performing sex: The representation of male and female musicians in three genres of music performance.” Psychology of Music 51.1 (2023): 188-225.

Conclusion

My goal is to provide a supportive environment for my daughter to counter gender selection biases. For music, that includes creating a learning opportunity for drums (if she wants, maybe bass and guitar too) and guiding that opportunity to minimize other sources of gender bias (e.g. by not following the orthodoxy of classical lessons).

References

- Hallam, Susan, Lynne Rogers, and Andrea Creech. “Survey of local authority music services 2005.” (2005). ↩︎

- Hallam, Susan, Lynne Rogers, and Andrea Creech. “Gender differences in musical instrument choice.” International journal of music education 26.1 (2008): 7-19. ↩︎

- Sergeant, Desmond C., and Evangelos Himonides. “Performing sex: The representation of male and female musicians in three genres of music performance.” Psychology of Music 51.1 (2023): 188-225. ↩︎